An attempt at defining the central theme of this blog. A way of looking at the world by aesthetic means that doesn’t stop short at mere aestheticism.

I don’t claim to have taste, but my distaste is beyond any doubt.

Jules Renard

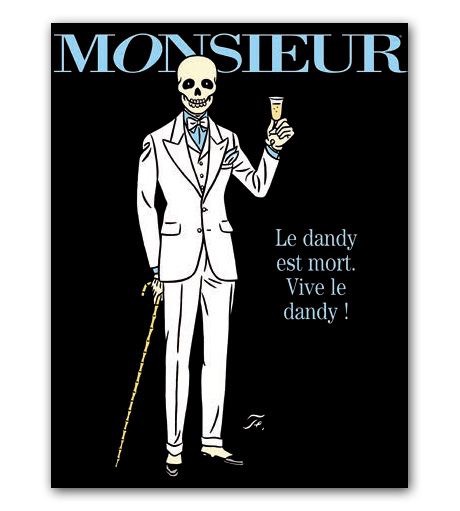

Voltaire was categorical: “Pourquoi ce garçon a-t-il toujours raison? Parce qu’il a du gout (Why is this boy always right? Because he has taste).” It would seem impossible to make such a claim today. While taste has always been an elusive notion, the twenty-first century has made it the last taboo. The democratisation of taste, which Baudelaire feared as the dandy’s death knell, happened long ago. While the twentieth century might have democratised taste, the twenty-first has killed off the notion altogether. To qualitatively discriminate in aesthetic matters today is a habit akin to necrophilia only less acceptable, lacking as it does the forced extravagance that pleases an unshockable cultural climate.

The notion of “good taste” developed hand in hand with the dandy. At the beginning of modernity, neo-classicism codified tastes in art, architecture and design. The concomitant codification of the gentleman in its artificial epitome, the dandy, was inextricably bound up with neo-classicism. Like the dandy, “good taste” was a bourgeois construct that exemplified the need of the emerging middle class to assert the superiority of its values over those of both the aristocracy and the proletariat. The Modern Movement of the twentieth century then tried to recapture the certainties of the rules of classicism, which the eclecticism of Victorian taste – viewed by modernists as the very definition of “bad taste”– had thoroughly obfuscated. The dandy’s existence was dependent on a notion of taste, and it was Brummell’s greatest achievement to have established this notion with such lasting authority. The parallels between “good taste” and dandyism are so manifold as to make the two well nigh synonymous. Taste as a description of discernment rather than oral sensation is primarily a feature of western cultures, based ultimately on the idea of a shared Greco-Roman heritage. Taste is an artificial construct, as it gives absolute authority to subjective perception: While Immanuel Kant maintained that aesthetic judgments have universal validity, the varied and paradoxical history of taste has shown that this is hardly so. Yet the narrative of “good taste” that begins with neo-classicism assumed its own universality with the same disarming implicitness that led the dandy to take it for granted that he was a gentleman. When “good taste” went through its Victorian decline, the dandy followed suit into decadence with great relish, until both were resuscitated by the Modern Movement. Oscar Wilde had already replaced exemplary elegance with affected eccentricity, so prefiguring the inauthentic “public dandyism” of today. Self-promotion and stylisation are characteristics of a celebrity culture that fundamentally lacks the capacity for reflection that alone could lend it authenticity. The Italian dandy Gabriele D’Annunzio had been one of the first to use the medium of photography for the purpose of self-propaganda. Ironically, after losing the sight in his right eye as the result of a flying accident, he subsequently became photophobic. Today any publicity is good publicity, and an aversion to being constantly photographed in a world that is deluged with images is considered quaint at best.

While the dandy of the twentieth century might frequently have asserted his individuality by sinning against “good taste”, his individuality still defined itself around the tension between the observation of rules and their transgression. Confronted with a world without rules, a world in which everything is permissible as long as it has had its claws removed, the dandy’s twenty-first-century epigone lacks the tension necessary to define his individuality. Concocting a persona out of the combined dressing-up boxes of history and fashion, when both are accessible without paying a personal price, is neither heroic nor subtle. In his curious mixture of asceticism and excess, the dandy was heroic primarily through his sacrifice of the chance of conventional happiness. While in the twenty-first century the concept of “happiness” seems more elusive than ever, this is the result not so much of a commitment to sacrificing on the altar of rules – aesthetic or otherwise – but rather of the disorientating lack of a dominant narrative to follow or disrupt.

Even the “secondary dandyism” of the late twentieth century, which Susan Sontag identified with camp subcultures and their celebration of “bad taste”, has become an irrelevance. There is hardly a subculture left that has not been taken up and exhausted by the mainstream. Tattoos, for example, no longer signify crime of the real or the aesthetic type; they are the stigmata of a culture in which the transgressive has become the banal convention. As Sebastian Horsley, one of the more convincing twenty-first-century dandies, put it: ”You make a mark on your body when you feel you can’t make a mark on your life.“To substantiate his existence, the modernist dandy relied above all on meaning, whether this lay in “good taste” or the declaration of the absence of meaning in itself (as with twentieth-century dandies with a penchant for existentialist absolutes). To assure himself of meaning, the dandy sought to make meaning identical with himself, to unite form and content, to find himself and consequently to become identical with himself. Kierkegaard thought “desperately trying to be oneself” the hardest task there is, and it is a truth universally acknowledged that the advice to “just be yourself” is impossible to follow even for the most superficially reflective person. Yet both the dandy and the notion of taste relied on the existence of self, however elusive. The nineteenth-century rationalist architect Viollet-le-Duc even maintained that taste and the self were identical: “Le goût consiste en paraître ce que l’on est, et non ce que l’on voudrait être (Good taste lies in appearing as one is, not as one would wish to be).“The twenty-first century, on the other hand, conveniently dispenses with the elusive task of becoming one with oneself and indulges in endless role play. The impossible dream is being dreamed no more.

Melancholy, man’s mourning of his own alienation from his timeless origin, was the mental state of modernity, and above all of its epitome, the dandy. He instilled meaning into this temperament either by giving himself up entirely to sensuality, by celebrating his alienated state, or by aiming for transcendence, by instilling the visible world and by extension himself with mystery. The twenty-first century has made meaning elusive, which is why attempts to regain it today so often combine great urgency with an awareness of their own futility. In the twenty-first century, melancholy has turned to depression and psychosis, barely held at bay by ubiquitous psychotropic drugs.

Ironically, the dandy’s creation carried his demise within itself; the weight of his Janus face was always going to break his neck in the end. Two souls lived within his breast, the epitome of über–aristocratic distinction on the one hand and the revolutionary harbinger of democracy on the other, he ultimately found that the seeds he had sown had turned into dandy-eating plants that would devour him. The dandy perpetuated the “ injustice” on which all high culture is based: he created parameters which privilege a minority. “Elegance is by its very nature not available to the majority. She certainly can appear to be modest, but she can never be ordinary without disappearing. In other words she is not democratisable.”After coming into being as a by-product of neo-classicism, “good taste” spent the rest of the nineteenth century as a criterion for judging the fine arts. Once the Modern Movement had resurrected the notion in the twentieth century, it eventually moved on to design – partly because “manners”, defined by moral principles (form follows function, integrity of materials), were first applied to design, and partly because the increasing abstraction of modernist art made principles of taste harder to apply. After the Second World War, “the public would take its aesthetic pleasures where it could find them: in the styling of cars, the cinema and in popular culture. Put another way, the century of consumerism has moved the entire man-made world into the province of aestheticism.“Halfway through the twentieth century, the democratization of taste had thus progressed so far that, according to a superficial definition of the term, a great part of the population of the western hemisphere displayed aspects of dandyism.

The shift from fine art to consumer goods, reached its first period of decadence in the 1980s, with the absurd commodification of the design object and of designers themselves, which thereby increased the banality of design – a vocation that had hitherto contained potential for originality – in proportion to its glorification by the market. When the market took over, taste itself started to be confused with fashion and “design”. The Loosian credo of perfectibility, of objects that last forever, gradually declined in currency in the course of the 1970s, along with modernism and the belief in progress. It was also in the 1980s that the concept of authenticity first dramatically lost its relevance, and a by then moribund modernity gave way to uninspired and equally lifeless regurgitations of the past. Today the whole of history has been made available for unreflecting consumption. If dandyism has followed a trajectory from revolutionary to reactionary to meaninglessness, so too has aesthetic culture as a whole.

The twenty-first century has seen the return of Art, but it has come back as a zombie. Where Nietzsche had declared that the purpose of art was “for us not to perish in the face of the truth”, art today is conspicuously lacking in such metaphysical healing properties; it has lost its mystery. Art is now marketed in a way that makes it entirely indistinguishable from consumer – or more accurately fashion – items. The bulk of art is sold without any reference to its integrity as though it were share certificates with pictures on them, its market and re-sale value the exclusive measure of its desirability. Art is to the new millennium what pop music was to the 1960s and 70s, and design and fashion to the 80s and 90s. It is hardly surprising that what passes loosely as “the new dandyism” is incestuously bound up with the art world and reflects its values. Significantly, it is particularly in the art world that taste has become an irrelevance. Discernment, specifically in the form of distaste, is implicitly discouraged as undemocratic or politically incorrect, while democracy has become synonymous with saleability. Capitalism has made the lowest common denominator its cultural focus much more thoroughly than the Cultural Revolution or socialist anti-elitism could ever have managed. While social democracy still allowed for distinction within equality, free-market capitalism ironically does not: Theodor Adorno has noted the puzzling paradox that under capitalism taste is not autonomous, as one would expect of a system that promotes competitive individualism, but tends rather to be collective.Dandyism carried within itself also this aspect of its own destruction: Stephen Bayley has called neo-classicism “ the first consumer cult”.

The market requires that everything must be likeable, as everything must be saleable. While contemporary culture contains a diverting stream of absolute negativity, as in say the writings of Michel Houellebecq, it is so hyperbolic as to be no more than a well-matched counterpoint within the endless muzak of meaningless positivity. While it is perfectly possible to propagate cultural pessimism on Facebook, the automated response for reactions to this view is a “like” button.

Retro-culture has grown enormously since its 1970s inception, but is now completely subsumed within the fashion system. In the process, it has lost the fine irony of its pioneers, while an excess of virtuosity curiously gets in the way of sublimity. London and Paris are full of creatures in perfectly researched period outfits, but with a few exceptions they give the impression they will get back into jeans and fleeces once the fancy dress party is over. Bespoke tailoring has experienced a renaissance, and the number of people who are having their clothes made has not been so large since the 1950s. Sartorial advice is everywhere, and even the most subtly stitched furrow has been comprehensively ploughed. But it is precisely this exaggerated self-consciousness that precludes true elegance: leaving a hand-stitched buttonhole undone on one’s sleeve is a gesture of true vulgarity precisely because it sets out to draw attention to the generic market value of the suit, while at the same time ignoring its inherent value. Something that ideally has been carefully designed around the wearer’s individuality is rendered exchangeable.

What of the twenty-first-century dandy, then? While the market negates the existence of “good taste”, to the OCD sufferer there is still a “right” way and a “wrong” way of doing things. In his autobiography Dandy in the Underworld, a memoir that veers between the lucidity of Quentin Crisp and the entertaining dementia of Helmut Berger, the late Sebastian Horsley admitted: ”Tidiness has always been my vice and it meant I would never really be chic. Only a fool would make the bed every morning. I couldn’t help it. A complete meltdown would follow if the kettle was not facing due east. For me controlling interior space and keeping order in an inherently chaotic existence were intimately connected. As I got older, my craving for classification,seen in the uniformity of my clothes, the obsessive need for perfection in my work, and the symmetry in my art, was a means of staving off the chaos I saw at the centre of my being.” Born in 1962, Horsley found inspiration not only in a mother with “the loyalty we all feel to unhappiness”but also in the nascent punk movement of his teenage years. Sebastian understood that dandyism, like punk, was about flamboyant failure. Of Johnny Rotten, lead singer of the Sex Pistols, he observed: “He had all the unmistakable signs – the charismatic aura, the dandy’s narcissism, the canny look of the holy tramp.” Horsley soon merged into a convincing hybrid of punk and dandy. In adulthood he dabbled in anything transgressive – from passive sodomy with Scottish murderers to penetrating quadruple-amputee prostitutes, from offering his services as a gigolo to having himself crucified in the Philippines – without ever losing sight of the destination of his journey: himself. As self-scrutiny inevitably provoked exasperation as much as inspiration, oblivion proved to be the only passion that could balance his compulsion. A connoisseur of heroin and its twenty-first-century plastic cousin crack, Horsley was ever faithful to the vice that would kill him. In his forty-eighth year he died of an overdose, on the night of the West End premiere of a play based on his autobiography.

The Parisian illustrator and writer Floc’h was born Jean-Claude Floch in 1953. Old enough to have experienced the end of modernity and be a little wistful. Immaculately dressed in a suit that echoes the 1930s without stooping to fancy dress, he claims to have “stopped wearing jeans after a bad LSD trip”. He illustrates his own books and others in the irreproachably modernist style of the ligne claire, made famous by Hergé. Floc’h is also a great anglophile: his early bandes dessinées have titles such as Le Rendez-vous de Sevenoaks and Une trilogie anglaise. His apartment in the fifth arrondissement is decorated in the style that captures the essence of Britishness as seen from a distance, a beautiful abstraction that is unknown within the sceptred isle itself: what should they know of England, who only England know? Floc’h is a dandy in the grand tradition of classic modernism: he is passionate in his belief in perfectibility. Rather than playing the lottery of fully bespoke tailoring, he is an obsessive alterer, permanently tweaking existing garments to fit his vision. The strikingly well-fitting 1930s-style single-breasted suit he wears started life as a baggy 1980s double-breasted affair. Defining taste as “le don de discernement”, he is acutely aware that a dandy in the tradition of Brummell is an anachronism in the current climate: “From the 80s onwards we had to live with mauvaise foi,” he explains. The existentialist term perfectly describes the state of being at odds with the zeitgeist. Yet while Marxists used the term as “false consciousness” in order to alert those lagging behind history, the “right consciousness”, that wishes to be at one with the body it inhabits, is now itself history.

What remains of the dandy? Has all the good gone from the word goodbye? Baudelaire begs “every human who thinks to show me what remains of life”, and dandyism appears to be a form of life that is all but dead. For an enlightened resurrection we might turn again to Proust, whose concept of “regaining time” was described by Camus in terms of an alternative (to) religion: “It has been said that the world of Proust was a world without a god. If that is true it is not because god is never spoken of, but because the ambition of this world is to be absolute perfection and to give to eternity the aspect of man. Time Regained, at least in its aspirations, is eternity without God.” Where the modernist Proust tried to regain the spirit of the Belle Epoque of his childhood, today’s bourgeois rêveur seeks to recapture the consciousness of modernity itself. “Actively decadent”, he uses the disillusioning experience of the last three decades to come to a considered notion of taste. Aware that “good taste” and fashion are both constructs, he looks to his own past, his own moments of pain and inspiration to arrive at an intelligent notion of taste. Intelligent taste in the Proustian sense is “analytical intelligence mutated to a poetic sensorium” (Herbert Lachmayer).

In a world that has lost its grip on meaning, the dandy understands that taste is not an arbitrary collection of likes and dislikes, but rather a rare form of intelligence: an intelligence that transcends the ubiquitous knowledge of styles past and present. Gaining this intelligence is a perpetual process, which is part and parcel of the gaining of self-knowledge. But to have gained it, cela justifie une vie.

Featured image: Alternative cover for The Dandy at Dusk by Floc’h