By reinforcing the Dandy at Dusk’s definition of dandyism as a reflected relationship with the self rather than adoration of the golden calf of beauty our prodigious guest author is sure to confront the aesthetes. More so by removing the libidinous Nietzschean superman con salito cattivo Gabriele d’Annunzio from the canon of Italian dandyism and replacing him with a poet who was a nuanced as he was elusive: Guido Gozzano

A prayer to the good Jesus to suppress some imbeciles …

to obtain the neighbour’s wife…

to suppress my enemies …

to pull an evil prank …

not to be like d’Annunzio.

G. Gozzano

There is a longstanding cliché, in Italy, according to which dandyism is inextricably associated with Gabriele d’Annunzio (1863-1938). On the Southern side of the Alps, it is hard to imagine someone who, if asked ‘What is a dandy?’, would immediately think of George ‘Beau’ Brummell knotting his tie in the dark. In all likeliness, one would sooner cite Oscar Wilde and his Dorian Gray. Or perhaps even Des Esseintes, the decadent par excellence, protagonist of the novel À rebours, someone who, exiled in a villa inaccessible to the vulgarity of the outside world, spends his life in cultivation of supreme pleasures and most sordid vices with a sense of self-indulgence and a death drive so profound that in comparison the fleurs du mal fade away like greenhouse violets. The comparison with il Vate d’Annunzio’ superfine amusements, with his lovers and cocaine in the Vittoriale’s secluded garden, is compelling. After all, d’Annunzio the aesthete is but the prodigy of the same culture: the ‘naughty nineties’ of the 19th century, the decadents’ golden age.

Guido Gozzano (1883-1916), the Piedmontese bourgeois poet of kitsch – the ‘good things of bad taste’, as he himself dubbed them – was 20 years younger than d’Annunzio. The Italian cultural world in which he moved was still led, back then, by the latter. Gozzano, who quite early ceased to follow d’Annunzio’s model, scarcely has a reputation for being a dandy. And how could it be otherwise?

Accustomed as we are to d’Annunzio’s aestheticising mysticism, the extreme consequence of l’art pour l’art professed by Wilde’s late Romantic gospel, we cannot but perceive a marked and calculated difference in Gozzano’s poetry, inspired by melancholic nostalgia, by pretty ladies glimpsed at the coffee counter with whom the poet dare not begin a conversation, by cocottes that life has placed for us eternally on the other side of the gate. From the strong and bellicose colours of d’Annunzio’s Laudi, or from the libertine extremism of Andrea Sperelli, the unrepentant seducer from his Il piacere, too many have assimilated the paradigm according to which the dandy is akin to – if not one and the same with – a Don Juan, the luciferian hero, the Übermensch who makes absolute commandments of his own will. The lawyer Gozzano stands light years away, where he shines dimly, crepuscular like his whole generation, grown up in the zenith of d’Annunzio’s sun and therefore destined to shadow, the catabasis of poetry in the lukewarm everyday world, which at first glance may very well seem antithetical to lyricism.

It is, however, only an effect of said flawed cliché, which identifies the dandy with the epicurean superman, ostracising thereby the stoic to dusk. It is a secular and incorrect prejudice arising from a radical misunderstanding of what lies at the heart of dandyism. Recovering its full character, then, may correct an unjust exclusion.

If we wanted to go back to the source of dandyism in order to grasp its noyau dur, applying the genealogical method to a phenomenon that, just like a well tailored suit passed from hand to hand, cannot be understood apart from its first being bespoken, we would unanimously identify its progenitor as the aforementioned Beau Brummell. In Regency England, Brummell took on the permanent revolution of men’s clothing. Moving beyond the laces and pastel colours of the European courts that still constituted the essence of the male costume, Brummell championed instead the rationality of the English country gentleman’s suit: boots, ankle-length trousers, navy blue coat, ochre waistcoat, white shirt. This was not only to become the substitute, but the ideal itself, for the greatest revolutions take place in the invisible realm. Indeed, if it has been said that Brummell can be credited with the invention of the modern suit, it is not only the result of historical contingency (nor is it an invention in the strict sense of the term). Brummell fathered the idea of modern costume. The male suit has its roots in Neoclassical culture: the canon of its proportions, derived from Greek statuary, and the rigour of its lines and shapes, which eclipses the value of ornaments and decorations (‘Ornament is crime’ is the sentence erroneously attributed to dandy Adolf Loos, which nonetheless contains an element of truth), prove it beyond doubt. The suit’s character is as functional as it is cerebral.

Having become an archetype, which stands a retouch here and there but not forcible alterations, the idea of Brummell’s suit is still the quintessence of the male dress today, whether one likes it or not, whether one knows how to wear it or not. The tailored suit, although threatened by extinction, still embodies Brummell’s founding principles, some of which unconsciously persist on the millions of individuals who every day go to work in an off-the-peg model. Still it would be wrong to think that behind such a masterpiece there must have been an artist of sorts. Or rather: if Brummell was an artist, his work of art was exclusively himself. The perfection of his suit and the sprezzatura of his ties reflected his ruthless, brilliant irony and, above all, his impeccable and cenobitic taste, thanks to which he, son of a servants’ son, had made his way to the upper echelons of English aristocracy. Besides that, Brummell was incapable of anything amounting to toil, and it’s easy to imagine him being quite proud of that, too. He left his studies and military career, for which he had no inclination, never accomplished any work, had no defined artistic talent, and in his eyes everything he was forced to do in his life was little more (and little less) than an unbearable sinecure. The dandy is, and does not do.

As far as we know, Brummell never enjoyed the charms of a woman in their entirety and engaged in little to no vice at all. He loved beef and had a fondness for the biscuit rose de Reims, as well as a penchant for the gambling table (which was eventually responsible in part for his downfall), but his figure has nothing to do with the extremes of rogues and decadents. Brummell was by no means an aesthete. Doubtless he deserved the title of arbiter of taste, but beauty did not weigh on him like a categorical imperative. If there was beauty at all, it was an epiphenomenon of elegance, of the religious adherence to the canon of perfection. But if Brummell was neither an aesthete nor a decadent, then it turns out that the dandy himself – contra d’Annunzio – is not necessarily either.

Brummell’s way – and therefore the dandy’s way tout court – is an austere path to self-knowledge. Once realised, one is complete, which is to say useless and finished. A work of art, mirror of completeness, has no practical purpose, or, at any rate, thus thought the Beau and his acolytes. One does not add a line to a perfect book. But then, if on the surface the dandy seems most desirable for the perfection of his attires and the painstaking command of rules and etiquettes, it is actually a defence mechanism. On the one hand, the dandy transcends conventions by adhering to them with the utmost rigour: by forcing them to their extremes, he causes them to break, until what remains is the pure and irreducible individual. On the other hand, though, unable to adhere and to belong, contrarian by nature but not vexatious enough to be antagonistic, he understands that he is doomed to irrelevance and loneliness, and adorns his persona with inaccessibility. By giving the impression of choosing superficiality to mask an afflicted depth, he paradoxically declares that there is no difference between the two. He hides himself, embracing the rituals that define his shape, but remains a judge of tastes and manners through the irony that is the privilege of the defeated. Dandyism is a via negativa to oneself. It has nothing to do with affirmation, triumph, visibility. In Baudelaire, the dandy rightly takes the form of the flâneur, the unobserved observer, a prince in disguise ‘who everywhere enjoys his incognito’. Beau Brummell used to say that if someone notices how you are dressed, it means that you are not dressed well. The dandy can be recognised only by himself, and sometimes not even by himself, as ultimate proof of his fatal isolation.

In one of the most remarkable scenes of L’Education sentimentale, amongst peacocks and swells dressed up in the most eccentric ways to strut during a picnic in the park, Flaubert gives us a glimpse of an authentic dandy crossing the crowd with haughtiness, like an imperceptible and elusive epiphany. We recognise him – and we cannot err – for his suit: essential, minimal and, above all, black. It is, once again, Baudelaire who shrewdly notes how the dark suit of the dandy, and of the gentleman in general, is a visible sign of mourning. The dandy’s mourning takes on different configurations depending on the era in which he lives. With Baudelaire it enters the world as a response to modernity; for Fitzgerald it is the awareness of the proximity of death, which indeed awaited the hedonism of the 1920s around the corner of the decade; for Bunny Roger, Cyril Connolly, Evelyn Waugh and the rest of their generation, it is the reaction to the end of an era that will never return.

Decadence is a consequence of melancholy, never its conditio sine qua non. Melancholy alone is fundamental, may it be caused by what was not done or by what is no longer there, the temps perdu on which Proust wrote his summa of dandyism. But such black bile, taking many forms over the decades, from spleen to ennui, from Sehnsucht to Wanderlust and Weltschmerz, does not lead all down the same path. Philip Mann, in The Dandy at Dusk, lists four outcomes: travel, ‘artificial paradises’, sickness, death. The last is Jacques Rigaut’s way: he had set the date of his end in advance and had since walked with ‘his suicide in the buttonhole’ of his blazers. Jean Cocteau, Count Gottfried von Bismarck-Schönhausen and Sebastian Horsley, among many others, attempted to escape the blue devils with the mixture of drugs and perversion inaugurated by Des Esseintes. But for countless others, daydreaming worked just as fine: Quentin Crisp, for instance, described himself as too anaemic of will to yield to dissolution; Sándor Márai used to go to the train station to delude himself that he was about to leave for a remote destination; failed writer, tireless walker and master of solitude Robert Walser too belonged to this kin. In other words, d’Annunzio’s mode has never been the norm.

Wilde used to make his appearance donning richly decorated velvet jackets, tight breeches and bow-tied shoes – quite an insult to Brummell’s classicism, indeed everything the first dandy had tried to distance himself from. But it is once again Philip Mann who suggests that Wilde was only truly a dandy, and for the first time in his life, when he believed he had left dandyism behind, in the period initiated by De Profundis and continued after his imprisonment. The experience of conviction and of exile and his Catholic conversion allowed him to come to terms with his own limits, with renunciation and abstention. Up to that point, he had lacked the appropriate kenosis for the imitatio Christi he had longed for all his life. In that moment, the acquaintance with pain led the last Wilde to the awareness that life is a tragedy, while he had previously declared that he rather considered it a ‘brilliant comedy’. The visible effect of this change of perspective was the adoption of the Brummellian suit instead of laces, silks and velvet.

Now, it is obvious enough that a correct understanding of dandyism involves a revaluation of the canon. And within the Italian tradition, something akin to the later Wilde’s case might have happened with poet Guido Gozzano.

In his youth, Gozzano was charmed by the myth of the dandy as depicted by d’Annunzio’s vitalism. Laus Matris, a poem Gozzano wrote on the occasion of his 20th birthday, is Dannunzian through and through, from the title to the intertextual references, and most explicitly in the epigraph. Similar in inspiration, and almost equally the direct offspring of il Vate’s influence, are the hedonistic ode Vas Voluptatis and Suprema Quies’s morbid atmospheres. These were written during his lively student years, when he joined the ‘mad brigade’ at the Società di Cultura in Turin and read Nietzschean-inspired literature and Symbolist francophone poetry, all of which kindled his youthful spirit. And yet, a new poetics – ironic, melancholic and detached – was soon to arise after a ruthless clash with life and as a consequence of a Leopardian ‘appearing of truth’, which signalled the slaughter of juvenile illusions. Gozzano the poet possesses a rare lightness; he knows how to smile and shed a tear at the same time. ‘Life had taken from him all its early promises’ reads his Totò Merùmeni, ‘And though for years he dreamed of love that would never come | and conjured death by the hands of artistes and princesses, | today his lover is the adolescent maid at home’.

In his noteworthy study on Gozzano’s poetry, Italian critic Edoardo Sanguineti makes a crucial argument. Faced with the obsolescence to which all things are doomed by their transient nature, Gozzano chooses exile in a position that borders on paradox: treating everything as if it had already been made exotic and démodé by the passage of time. Objects and people, then, are observed with a bittersweet nostalgia, which highlights the havoc caused by temporality and allows for distance, coldness, and dissimulation. It is, however an all-too-easy mask, from which the poet returns more defenceless and fragile than before, exposed in his incurable inability to ever be satisfied. And what better refuge than useless objects for those who are indeed entirely useless?

In this sense, Gozzano’s work seems to share the spirit and intent of Proust’s Recherche. Gozzano too, armed with memories and sober elegance, looks backwards for a ‘muse of the time that’s already been’ in the midst of old photographs, once-luxurious impressions of the past, reminiscences of loves forever pending. It is an enterprise doomed to failure: thrice confirming Mann’s list of the consequences of mal de vivre, Gozzano died at only 33 of an illness that had plagued him for years, but not before attempting an unsuccessful exotic escapade in India.

Gozzano’s Indian letters fully display the gap between life and art, that is, between naturalness and artifice, which makes them the privileged and perhaps unsuspected site wherein to verify the author’s dandyism. On one side, the luxuriant nature of the tropics terrifies the stereotypically urbane European; on the other, what he observes seems to imitate his wildest fancies, the orientalist dreams with which he grew up. ‘If I go back to the earliest origins of my memory’ he notes, ‘I see the sacred city depicted in a Napoleonic woodcut in my playroom. And the memory is so clear that the dream of that time seems to me to be reality, and the reality of today seems like a dream…’. He then quotes Wilde: it is not art that imitates life, but it is life that becomes just like art. Such mimesis, however, is quite obviously doomed to remain forever incomplete: between dreams and reality – the first being the perfect image of the dreamer, the second something unknown, elusive, totally different – there remains a gulf that generates disappointment and disavowal. Gozzano prefers the reading room of Bombay’s Hôtel Majestic to real travel, to the mud and the heat that would only spoil his clothes. What else could we expect from a dandy en voyage? He has no intention to have his own say on India; instead, he rearranges and counterfeits the words of others, sometimes already second-hand orientalist chronicles and reports, to which he adds the lustre of his own style. As a result, his letters from India are studded with errors and gross inaccuracies, and yet, this does not corrupt the core of the ‘reportage’, which is more truly a descent into himself than the record of an excursion in a foreign land. Most of the scenes which he claims to have witnessed happened in places where he did not even set his foot; he preferred to write about them as if he had actually seen them, sticking to all the worst and best tropes of exotic literature, here taken to sublime levels. For the point is exactly this: as he knows that reality fails us most of the time, he cannot risk being disappointed again. He advises: ‘Do not forget to complete with the dream the meagre pleasure bestowed by reality!’. Gozzano is nostalgic about a time when travelling was just like dreaming. As Sanguineti points out, he seeks ‘the great escape from bourgeois prose’, prompted to motion by the only force that can prompt him: the ‘reactionary longing for the lost past, the decadent dream for distant lands, the hatred for l’âge actuel’.

Going back to the initial hypothesis, the idea that there was more dandyism in Gozzano than in d’Annunzio. Like the fairy tales’ hero, Gozzano could reach the promised treasure only when he thought he was the furthest from it. ‘If I think that were I not Gozzano,’ he confesses to God in the poem L’altro, ‘pure, foolish and coarse, | you could have made me gabrieldannunziano: | that would have been so much worse!’. If the hypothesis is correct, it is because there is more of the original dandy in provincial Gozzano than in d’Annunzio the aesthete. Mario Praz reminds us that d’Annunzio, a native of Abruzzo’s wilderness, was deep down a savage, mainly meant for war and recklessness. Too flashy and not sober enough to fully adhere to Brummell’s chaste principles. After being fondled by Paris’s café society, the mondaine world to which belonged Robert de Montesquiou (the larger-than-life figure behind Proust’s Baron de Charlus), d’Annunzio opportunistically exploited the First World War to fashion himself a reputation as crowd-inciter, daring fighter, valiant hero and State provocateur. He was without doubt very good at making himself a character from a 19th century novel, but, from the point of view of dandyism, he did too much. The dandy knows that he is useless, hence he attempts nothing. He is a character from tragedy, we said, not from epic. It is perhaps for this reason that in the anguish-fuelled prose of Il libro segreto, d’Annunzio too, at the end of his mortal existence, reaches the bitter realisation: ‘This feral teadium vitae comes from the need to run away from the annoyance – which today is little less than terror – to have been and to be Gabriele d’Annunzio’.

The awareness of not being able to escape from himself and his destiny shines through in every line of Gozzano’s work. ‘What I pretend to be and am not!’, thus ends his masterpiece, La Signorina Felicita. Lavish vestments are no longer needed: according to Giuseppe Scaraffia, Gozzano’s strain of dandyism is delicate and disenchanted (‘ironic and subdued, he dressed discreetly’, resorting, for a splash of flamboyance, to a sober white safari suit). Nor does he need an archaic or courtly language, that of d’Annunzio’s ‘superliquified’ words. Gozzano can transmit the rhythm of actual speech without renouncing versification, as in the poem Le due strade: the dialogues are anything but unnatural, yet the metrical scheme is in refined alexandrines. The same happens in his fairy tales, which too present a mixture of poetry and prose, or rather, an elevation of prose to poetry through ironic dissimulation. For Baudelaire, even Monsieur Bovary, the mediocre, provincial husband to a compulsive cheater, eventually reaches sublimity, and there lies the value of Flaubert’s novel, precisely in its sublime form of dandyism, that elevates the provincial and prosaic to tragic perfection.

Gozzano, therefore, fully belongs to the dandy’s cold sect by virtue of the very reasons for which he abandoned the Dannunzian model: a sober and elegant detachment from a life forever unsatisfying combined with the inability to do and to love (‘I love but the roses | that I did not pick’, and also: ‘I cannot love, you silly! | Never have I loved, | never! That is the bane that I hide’). Having lost the essence of dandyism along the way has mistakenly excluded him from the canon, when, perhaps paradoxically, he belongs to it precisely because he tried to move away from it, or at any rate from its decadent bloodline, embodied, in Italy, by d’Annunzio. Nothing is more dandy than abjuring dandyism. But what, then, is the dandy?

In his monumental and unfinished studies on modernity, the Passagenwerk and Charles Baudelaire, Walter Benjamin comes to the conclusion that the dandy is today’s hero – or rather, in any other time he would have been a hero. However, born under the sign of modernity, he is forced to abdicate and go into the exile of his own uselessness. ‘Modernity’ says Benjamin ‘proves to be his undoing. It has not provided for the hero; it has no use for his type. Modernity anchors him forever in the safe harbour; it abandons him to an eternity of idleness. In this, his last incarnation, the hero appears as dandy’. Gozzano is then perfectly consistent as the dandy of coffeehouses and bicycle rides, the proper emblem of the absolute idleness of a hero at rest in a time vacuous and prosaic. Nothing could be more different from d’Annunzio, propagandist and connoisseur of the Zeitgeist and yet a hero from a previous age, inasmuch as he was consequential in his heroism. Gozzano, to the contrary, is the prototype of ineptitude, exiled by sickness, renunciant by necessity (about this topic, he even drafted a screenplay – unfinished – on St. Francis), that hides his aristocratic sceptre in the masking of twilight. His vow of regret transcends failure: it is the sign of an irreducible distinction, a faithfulness to the Brummellian principles so often ignored or betrayed by rakes like d’Annunzio.

When Gozzano speaks to his ‘sweet sadness’, he finds that there is nothing ‘sadder than never being sad again’. And yet, when only a graceful albeit poignant irony remains in place of even tears, then it is really the dandy who speaks, the one who made himself a work of art: the perfect, complete, useless and smiling enemy of time.

Translation from the Italian by the author

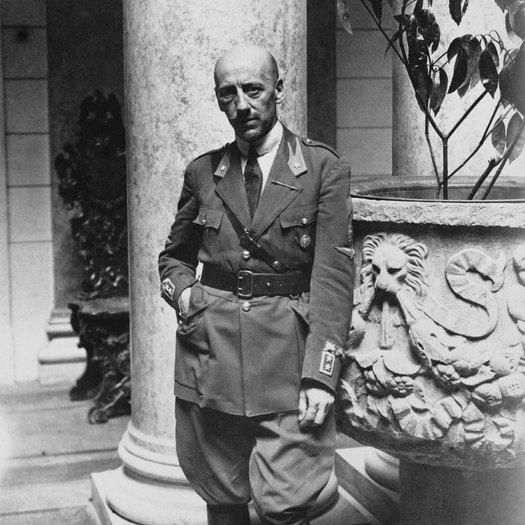

Featured Image: Not averse to pussy but not grabbing it either: Gozzano