Probing the dandy’s ambiguous yet potent sexual appeal

I want the adoration of my person to reach the point of physical desire.

Comte Robert de Montesquiou-Fezensac

Yeah we all need some one we can cream on, and if you want to, well you can cream on me.

Jagger /Richards

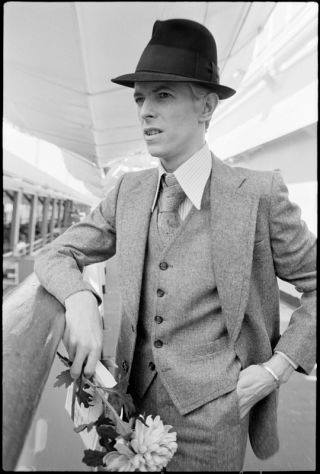

Quizzed on the subject almost any woman will tell you that she finds nothing more off-putting in a man than physical vanity. Being admired for one’s appearance is thought to be the female’s domain and male beauty of the epicene kind in a partner is thought to be unwanted competition to all but the young girl and the woman of a certain age. The latter will pay good money for a fine specimen. But the proof is in the creamy pudding: the most outrageously flamboyant peacocks have and had their female suitors moistening their drawers big and small. Few twentieth-century males could have excited as much desire and adoration in somewhat indistinguishably intermingled portions as Bowie did; in his contemporaries and generations after. If he was equally desired by men this acted only as a spur to any red-hot female: no woman has ever been put off by the size of the competition for an object of desire. Indeed – and this might be a caveat – female desire has a tendency to go with the flow of the times: at some stage in the mid-1960s, it quite effortlessly moved down several stone and about a foot from Rock Hudson’s ‘trustworthy masculinity’ to Mick Jagger’s beau-laid boyishness (James Dean a decade earlier had mostly appealed to the aforementioned teenagers). The irony here doesn’t need pointing out but even if the beau in question’s self-admiration extends to his own gender some game girls are not deterred. By the mid-1970s Elton John and Freddie Mercury were out to all but the most naive. They still managed to acquire notoriously game (as far as forgiving little irregularities is concerned) German girlfriends/wives almost despite themselves.

The type of male that craved the sort of universal and unspecified adoration the pop-star did in the second half of the twentieth century in an earlier, pre-media age was the dandy. Even more culpably to some, he craved it for its own sake. One would have to say though that his audience was by necessity less pop and more what one might carefully call smart. The above cited Robert de Montesquiou is held to be the strongest real-life inspiration for the – apart from Swann – dandiest character in the Recherche: Baron Charlus. And if Beau Brummell was the Übervater of dandyism per se, Proust must be considered the godfather of twentieth century dandyism. Marie Joseph Robert Anatole Comte de Montesquiou-Fezensac surrounded himself with an adoring circle of society lionesses, Baronesse Adolphe de Rothschild, Countess Potocka, Marquise de Casa-Fuerte, Princess Bibesco, along with his dearest friend and cousin, the Countess de Greffulhe (Proust’s model for the Duchesse de Guermantes) as well as the cream of the literary and artistic set, Luisa Casati, Elonora Duse, Judith Gautier and Anna de Noialles. He was adored not only for his flamboyant personality: ‘tall, black-haired, rouged, Kaiser-moustached, he cackled and screamed in weird attitudes, giggling in high soprano, hiding his little black teeth behind an exquisitely gloved hand – the ‘poseur’ absolute’ but also his exceedingly florid poetry. While some of the above-mentioned dames might be considered society ‘fag-hags’, Sarah Bernhardt, the most feted woman of her age, actually managed to consummate her passion for this most unlikely object. Rather unflatteringly for the great thespian it is also related that the Comte de Montesquiou vomited for an entire week after congress had been achieved against the odds.

George Bryan ‘Beau’ Brummell, the first dandy and inventor of modern male costume was a product as well as producer of neo-classicism. Neo-classicism, the celebration of antiquity starting in the late 18th Century, also led to a reappraisal of the physical ideal aspired to by the ancient Greeks, as might be admired in the figures of the Parthenon frieze and the Apollo Belvedere. The system of clearly delineated limbs, heads and muscles, of harmonious stomachs and buttocks and breasts that was perfected in antique nude sculpture was adopted as the most authentic vision of the body, the real truth of natural anatomy, the Platonic form. It was indeed from these idealised versions of the male form that Brummell took his vision of the modern suit. Brummell’s rise in society was facilitated by his friendship with the Prince of Wales, which though certainly platonic, was founded on impulses that were aesthetic: they were united in their obsession with the sensuality of external grace. Hence the assumption that Brummell was homosexual, and even that the dandy as such is homosexual, is ever close at hand. Indeed the cultural historian Egon Fridell posited that the whole of classicism was homosexual in its approach: ‘The homosexual eye predominantly sees contour, usage of space, outline, beauty of line, plasticity. The homosexual eye has no sense for dissolved form, blurring valeurs, purely painterly impressions. And so, looked at in the bright light of day, the whole idée fixe of classicism stems from the sexual perversion of a German provincial antiquary.’ He is of course referring to Johann Joachim Winckelmann, the archaeologist and spiritual father of neo-classicism, who had the following to say concerning gender and the appreciation of art: ‘I have noticed that those who are solely aware of the beauty of the female sex and are hardly or not at all touched by the beauty of our own gender, are not usually blessed with an easy, lively and general appreciation of beauty in art.’

This might well be the origin of the hoary old tale that the only man with taste – the very origin of notions of ‘good taste’ can be traced back to the neo-classical moment – is the the gay man.

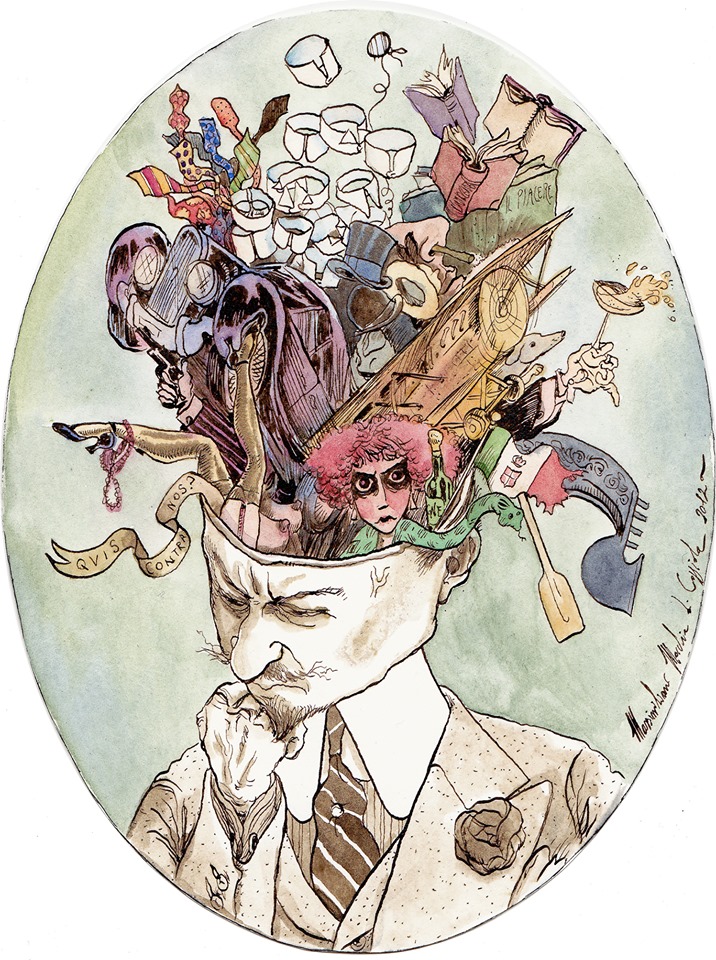

His origins in masculine-dominated classicism do not necessarily draw the dandy to homosexuality.Barbey d’Aurevilly,great French theorist of dandyism, dandy, romancier and great lover of women, with the marvellous title Une viellle Maitresse in his oeuvre, answered the challenge of homosexuality with characteristic ambiguity: ‘My tastes lead me there, my principles would permit me, but the ugliness of my contemporaries disgusts me.’ It is far more his leaning towards the cerebral – the rational paired with an over-developed sensibility directed exclusively towards the goal of aesthetic perfection – that makes the dandy wary of sensual abandon in the realm that he regards as his very own: Taste. Hence it would be truer to say – contre Winckelmann – that the dandy is careful to separate his aesthetic preferences from his erotic ones. According to Baudelaire, the second of the two great Frenchmen who have explained Brummell’s invention to the English, woman – on account of her proximity to nature – is the opposite of the dandy: ‘When woman is hungry she wants to eat, when she is thirsty she wants to drink, and when she is in heat, she wants to be fucked.’ If Baudelaire here (Mon coeur mis a nu) likens woman to an animal in what could be construed an unflattering manner, he in a more thorough investigation (La Femme straight after Le Dandy in Le peintre de la vie moderne) at least likens her to a beautiful animal citing his teacher Joseph de Maistre. He goes on to praise her as a deity, a planet that rules the world of the imagination in the male brain. Separating woman from the type of pure beauty that the sculptor in all his serious musings might dream up (‘Winckelmann and Raffael don’t concern us here’), he yet puts the feminine mystique and even its depictions above it. As far as the dandy his concerned Baudelaire grants him the abstract and melancholic embodiment of beauty that is the antique as well as the eternally modern one. On account of his idleness he also portrays the dandy as the ideal subject as well as object of love: as without time and leisure love can be nothing but a petit bourgeois orgy or the fulfilment of conjugal duties.

Yet it is true that in his search for aesthetic unity the dandy frequently seeks to overcome the female principle by either ousting or incorporating it. An androgynous appearance and a vaguely effeminate manner serve to adorn him (indeed effeminacy to this day remains a characteristic of the Englishman’s portrayal of cultivated masculinity quite independent of his sexuality). According to Barbey, Alcibiades himself had been one of the first androgynes of history ‘the most supreme example in the most beautiful of nations’. The appeal of androgyny, without doubt, lies in its universality: the androgyne is the object as well as the subject of sexual desire. The androgyne attracts by his self-sufficiency, the complete absence of need: a man who conscious of his own seductiveness doesn’t find it necessary to seduce. It is this universal appeal that puts the androgyne closer to the divine than mere man: something well understood by the third-century Roman emperor Heliogabal, who when he ascended to the throne age fifteen marketed himself not only as hermaphrodite but also as sun-god. Antonin Artaud explained the peculiar power of the boy emperor’s dual nature thus: ‘Heliogabal is man and woman. And the worship of the sun-god is the religion of the man, who without the woman – his double in which he is reflected – can achieve nothing . . . Within Heliogabal a struggle is taking place: the whole which splits itself and yet remains whole. The man who becomes woman and yet eternally remains man.’ Before his light was put out at the age of merely eighteen by the Praetorian Guard, the sun-god had managed to marry both a Vestal Virgin and a gladiator.

It seems that Beau Brummell maintained mostly platonic relationships with women – he was a close friend of Georgiana, Duchess of Devonshire, and Frederica, Duchess of York, remained a strong support throughout his time of exile. It is not known whether this apparent lack of amours was the result of a bad experience. What is clear, however, is that the possible consequences of love – a wife and children – would have meant an unbearable atavism for someone who had already divested himself of his birth family. Just as parents and siblings had hindered his self-realisation, a wife and children would have hindered his self-cultivation. Even if we assume that he would have been capable of an amourette within the confines of the rules perfected by the 18th century, he was clearly no Valmont. In his recent biography of the Beau, Ian Kelly begs to differ and suggests that sexy games extended beyond the card tables of Brook’s and White’s. Kelly indeed assures us that the melancholy madness that took hold of Brummell in his later years was the result of heterosexually acquired syphilis. Whether he died of syphilis or not, Brummell’s sad end was on the cards. His last game was always going to be a losing one. And so the dandy also has the aspect of an homme fatal. Drugs, alcohol, mental illness and suicide are the fleurs du mal he wears in his buttonhole. Like with his female eqivalent, the femme fatale, the predictability of perdition adds to his appeal.

Probably the most notoriously hetero-sexually active dandy was the poet, novelist and sometime political activist Gabriele D’Annunzio. Though the ‘confessions’ of men are as inversely unreliable as those of women as far as the quantity of lovers is concerned, d’Annunzio’s claim of a thousand might have been not too far from the truth (Let’s not forget that Georges Simenon already claimed 10.000 by the age of fifty, which with also about 400 novels under his belt must have made for an awfully busy schedule). Amongst them were apart from his wife and his long-term lover the great actress Eleonora Duse, contemorary luminaries like Isadora Duncan and the ballerina Ida Rubinstein. The seduction of the latter was initiated at one of her post-performance soirées in a manner best described by the man himself : ‘Seeing at close quarters those marvellous naked legs, with my usual boldness I threw myself to the ground and — quite oblivious of my swallow-tail coat — kissed the feet, rose, still kissing, from the ankle to the knee and up along the thigh to the crotch, kissing with lips as swift and supple as a flautist’s scurrying over the stops of a double flute.’ If crotch-kissing on sight doesn’t work for everyone, you’d think it certainly wouldn’t work for a completely bald , 5.4” homunculus with ‘eyes like blobs of shit’ (again Sarah Bernhardt) and teeth the colour of absinthe. But such is the eternal mystery of woman. In admittedly rather undandyistic manner d’Annunzio not only managed to make every woman he spoke to feel that she had his undivided attention and that indeed he was relaying state-secrets to her but also whisper the most elaborate compliments in her ear. It appeared that he had the most beautiful voice which must have helped. Also in his ample wardrobe, the remnants of which are to be admired in the Vittoriale, his impressive if less than tasteful villa at Lake Garda, he shunned the dandy’s habitual abstraction: Amongst the suits, uniforms and boots we also find a nightgown that has a sizeable gold-rimmed hole cut out for his cock and house-slippers decorated by an abstract rendition of the same.

While rumours that d’Annunzio had the lowest pair of his ribs removed in order to be able to suck the most treasured of his countless possessions seems to be unfounded it would appear to be true that onanism would be the form of sexual pleasure most suited to the dandy. It was Jean Cocteau who had developed this ancient art into a party-trick almost presentable in polite society: Lying down on the floor in front of the other guests he managed to make himself come without any visible stimulation. This ‘look: no hands’ approach to the most literal expression of self-love must certainly be granted space in the sublime realm the dandy inhabits. Quentin Crisp indeed regarded sexual-intercourse a poor substitute for auto-eroticism. He also puts forward onanism as an example of what is after all the dandy’s real art, containment: ‘Masturbation is not only an expression of self-regard: it is also the natural emotional outlet of those who, before anything has reared its ugly head, have already accepted as inevitable the wide gulf between their real futures and the expectations of their fantasies.’ A great masturbator as well as a great fornicator was Soho’s very own, late and much missed Sebastian Horsley. One of the more convincing 21st century dandies, Sebastian dabbled in everything transgressive: from passive sodomy with Scottish murderers to penetrating quadruple-amputee prostitutes, from offering his services as a gigolo to having himself crucified in the Philippines. All of which only added to the allure of the homme fatal and his appeal to the opposite sex. An aficionado of large mammilla Sebastian liked nothing better than locking himself in his room with a crack-pipe for weeks on end and spanking the monkey with the DVD player turned on to giant jugs. But when me-time got to draining he equally managed to gather some marvellous real-life examples around him. Most of them still alive. Unlike Sebastian who- ever faithful to the vice that was going to kill him – succumbed to an overdose in his forty-eighth year. Let’s hope for him that the dandy underworld is well stacked.

First published in the Amorist, 2018